Excerpt from the “Nearly Complete Guide to Multiverses, Quantum Choices, and That Feeling It Could Have Gone Differently”

Parallel Worlds

Noun | /ˈpærəˌlɛl wɝːldz/

A state of potential simultaneity with an uncertain point of reference. They may exist. Or not. Or both.

Often described as coexisting realities – in truth, more likely skewed, delayed, or overlapping. Those who perceive them are part of them. Those who don’t, possibly too.

Used in quantum physics, science fiction, and whenever someone wonders if there’s a version of themselves who’s slightly less irritated.

Caution: Parallel worlds may increase existential pressure.

Symptoms of prolonged thinking about parallel worlds may include: disorientation, déjà vu, identity suspicion¹, and existential side aches².

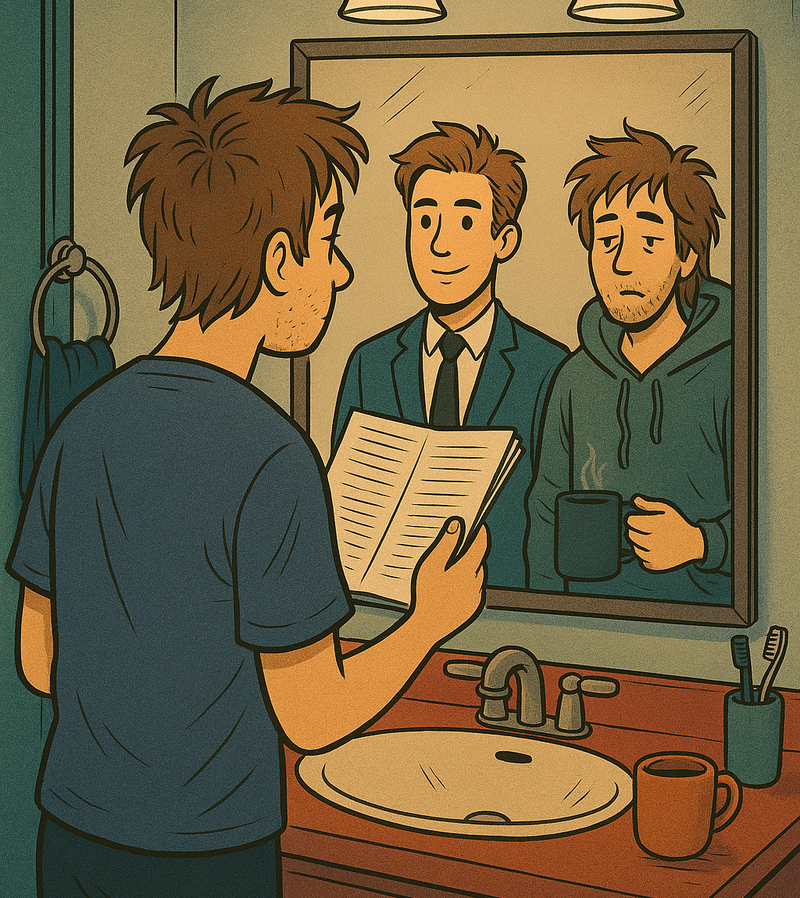

¹ Identity suspicion: The fleeting sense that you're not quite the person you think you are—or that someone else knows a version of you who isn't you. Most common in mirrors, old group photos, or family gatherings.

² Existential side aches: A vague pulling sensation in the region of lives not lived. Often arrives quietly—while passing missed opportunities, empty train platforms, or while sorting through old emails.

Parallel worlds have become such a popular concept that not believing in them almost feels impolite. Yet popular notions tend to overlook the essential. Parallel worlds are not alternative TV channels you can casually switch between. Nor are they backup versions of reality in case the main file crashes.

In physics – more precisely, in the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics – they are considered a possible consequence of every decision, every interaction on a subatomic level. Every event, no matter how tiny, creates a split. Not hypothetically – but as a real, though unobservable, possibility. A world does not come into being because it was planned. It comes into being because it was not prevented.

These worlds do not exist next to ours but overlap with it – like invisible layers, separated only by perception. The question of what is real does not get easier to answer. On the contrary: reality becomes a function of observation. Only what is observed takes form – the rest remains in the realm of possibility.

A world, then, is not a fixed entity but a decision that continues. Whoever looks, chooses – not consciously, but effectively. What appears linear to us may simply be the result of selective perception. That does not mean all worlds are equal or enduring. Some remain faint, unfinished, brittle. Others gain density – through experience, attention, through lived life.

What remains real depends not only on the moment of decision – but on whether someone holds on to it. That applies to physical systems just as much as to human constructs. A situation exists only as long as the people involved keep it going.

This includes diplomatic alliances, marriages – and in particularly precarious cases: leftover chocolate (a frequently reported phenomenon, though I must admit I have yet to confirm its occurrence outside of the lab).

Where decisions concentrate, worlds may collide or branch off. What is real for one may have long passed – or not yet happened – for the other. Two people, connected by memories, may find themselves in different realities without either being “wrong.”

Some of these realities are the result of deliberate decisions. Others emerge by accident – through a movement, a thought, a flicker of doubt at the wrong moment. They are neither stable nor arbitrary. And not every possibility becomes a new universe; some are as fleeting as a leaf, still clinging to the branch until the next gust of wind.

The idea that there could be countless versions of ourselves may feel comforting – or unsettling. But perhaps it’s not about what could be. Perhaps it’s about what is, because we experience it. Not because it exists objectively, but because we are in it – and because we remember.

Question to go:

Is what we call reality a fact – or a decision we keep making, again and again?

Kommentar hinzufügen

Kommentare